Quick Summary

Addressing victim, rescuer, and persecutor roles in teams can transform dysfunctional behaviours, fostering accountability and driving business growth.

Takeaways

- Dysfunctional team behaviours like ‘victim’, ‘rescuer’, and ‘persecutor’ roles hinder business growth.

- Cultivating accountability improves team dynamics and performance.

- Open communication is vital for addressing and resolving toxic patterns.

- Strong leadership fosters a healthier, growth-oriented work culture.

‘It’s not my fault I missed my target.’ ‘There was nothing I could do.’ ‘All the world’s against me.’ Recognise these traits? They’re classic victim behaviours. Over forty years ago, Stephen Karpman developed his ‘Drama Triangle’ of victim, rescuer and persecutor and it’s as relevant now as it was then.

These behaviours are toxic in the workplace. They breed ‘them and us’ cultures. We see it so often in companies – it’s endemic. We talk to someone in the organisation and they use the term ‘Management’. Alarm bells ring. Victim language. It sounds like British Leyland in the 1970s! The ‘workers’ feel justifiably persecuted by ‘management’. They go through life, thinking it’s everyone else’s fault. And by doing this, they never realise that they have control over their reactions and emotions.

Lack of personal accountability is everywhere. You see it in people’s reaction to COVID. In our view, it’s got worse in the past year. ‘We are all victims’ seems to be a popular narrative. ‘There’s nothing we can do’. We abdicate responsibility to the Government and blame them when they get it wrong. We make excuses for our poor health as a nation and expect the NHS to pick up the pieces. When a virus is rampaging, that’s more deadly to overweight, unfit people; we eat and drink even more. And exercise less! Yes – life is stressful. It’s been an awful year. But we all have the power to improve our health and minimise our risks.

If you’re struggling with dysfunctional behaviours in your teams, there are things you can do. And you need to do them quickly before they spread. So, let’s explore what these behaviours are and how you can fix them.

The Karpman Drama Triangle

We use this nifty exercise when we’re coaching teams and see victim mentality popping up. The Drama Triangle is used in psychology to describe the insidious way we present ourselves as ‘victims’, ‘persecutors’ and ‘rescuers’ in relationships. All are roles in a drama we unknowingly create and may not be accurate to who we are. But it’s easy to get stuck in a cycle that’s hard to break.

The victim sees life as happening to them and feels powerless to change anything. In many cases, this is a learned behaviour going back a long way. Children play this role brilliantly – they break something but give you a hundred reasons why it wasn’t their fault. Often there are tears!

The persecutor is always blaming and putting the victim down. They’re very self-righteous and quick to judge. Ironically, by placing the blame on the victim, the persecutor avoids any accountability themselves. When the victim says it’s not their fault, the persecutor will go on the attack. This is often where the initial conflict comes in.

And finally, the Rescuer feels terrible if they don’t intervene. They feel compelled to help the victim and diffuse the tension. But this has the negative effect of keeping the victim dependent on the rescuer. They never overcome the challenge and this allows the victim to carry on failing. It also feeds the rescuer’s ego – I’m such a good person because I sorted it out.

Where does the Triangle show up?

Often, the unfolding drama perpetuates a learned style of relationships. The people involved can’t step back and see what’s happening when they slip into the cycle. It keeps perpetuating around and around, becoming the norm. John pokes Betty and Susan jumps in to save Betty. Over and over again. The team becomes paralysed to overcome the problem.

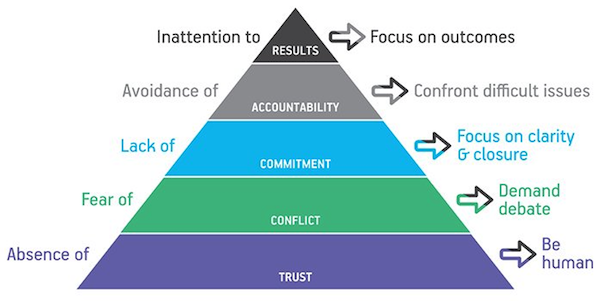

We see it in quarterly review meetings when coaching executive teams through Lencioni’s ‘Five Dysfunctions Of A Team’. As we move through his pyramid towards accountability, it might show up. Mainly when someone on the team is failing to deliver on their promises or metrics. It’s clear that they’ve turned up to check-ins every week, saying they’re on track, but at the end of the 13 weeks, they give a catalogue of reasons why they’ve failed. And none of them is their fault. As they play the victim, someone will try and hold them to account. The conversation gets uncomfortable and immediately, someone else jumps in to try and rescue them, maybe through humour or siding with the victim.

If there’s inattention to results, the Karpman Triangle becomes so valuable. It’s essential to recognise why it keeps happening. And do the work necessary to resolve it. There might be a known tension between two people in the team that makes everyone else feel uncomfortable. The drama between them becomes the focus instead of fixing the unlying problem that caused it.

Moving to the centre

So, what do you do to intervene? We suggest moving to the centre. Recognise the pattern of behaviour and get everyone to agree that they’re not going to use humour to change the subject when things get tricky. They need to get over their belief that it’s impolite to put pressure on someone else. Maybe it’s because they’re afraid the spotlight might be turned on them. But they need to stop trying to diffuse tension with humour or changing the subject.

Take out any exaggerated language in the conversation, ‘It’s all broken’, ‘We’re f*cked’ etc. Keep to the facts. Then the victim won’t have anywhere to go. They’ll be forced to answer specific questions. ‘You had 13 weeks and at no point did you say you were stuck – why is that?’ or ‘We’re all busy – what is it that went wrong?’ Take the emotion out of the situation so that people don’t have the space to create a drama. Don’t let tears derail the session and work through the discomfort.

Broaden the discussion out to the whole team so that there’s less focus on one person as the persecutor. Try to take out the ‘You’re wrong, I’m right’ angle. Bring in a bit of peer pressure instead.

Committing to zero triangulation

Decide as a team that triangulation has no place in your business. This means no negative conversations behind people’s backs. Commit to open, honest communication. And fire the people that can’t stick to it. Our experience is that it rarely gets to that point though. The people who continue to flout this rule start to play the victim. ‘This is ridiculous – it’s so childish’ etc. They fight against the new way of doing things but, if the team holds firm, they either change or leave. They’ve broken the rule and you’ve shown them it’s not acceptable.

Sounds easy, but it’s actually deceptively complex. In the UK, it seems we’re programmed to avoid candid conversations that make us uncomfortable. Yet it’s so important to tackle things honestly as soon as they crop up. And directly to the person’s face. You’re working towards an environment of radical candour, where your employees feel safe enough to show their vulnerabilities. This is how you build personal accountability – by giving people the space to be honest.

Identifying the behaviours holding you back

We’ve written about the ‘Sabotage Exercise before. It’s a great way to gain collective recognition of dysfunctional behaviours that you’re no longer going to tolerate in your team. By imagining they’re working for a competitor who’s sabotaging your company, your team will identify many of the things that are holding them back. Such a great ‘wow’ moment! Suddenly, they realise what they’re unknowingly doing to themselves. Once you have this, it’s a natural step to agree to stop these behaviours that undermine their performance.

It gives you a vocabulary and mechanism to hold people to account. One of the natural conclusions is a team charter. This helps unpick the drama. There’s a genuine commitment to each other. And if there’s inattention to results, it enables you to say, ‘Was that not the promise you made? How can I help you to keep your promises in the future?’ The relationship moves towards one of coaching. Maybe the team member is failing because something’s wrong in the structure of their role, or they don’t have enough specificity in their OKRs. You can help them with this.

Getting clear on positive behaviours

It’s often said that culture is what people do when nobody’s watching. So, it makes sense to codify your culture and get clear on the Core Values you want it to represent. If you can work out what you believe in, it follows there are behaviours that underpin these things.

We’ve talked before about Jim Collins’ ‘Mission to Mars’ exercise. In this, you identify the heroes from your company that you’d send to Mars. They need to represent the DNA of your organisation. Their behaviour should embody the very best of your business. If your whole team agrees on this, you can then define the behaviours that you value.

A good set of behaviours can then guide everything you do – hiring, firing, promoting and rewarding. And they will help you identify and manage toxic employees. With this in place and zero triangulation, they’ve got nowhere to go. They’re either going to have to behave in the right way and deliver or they’ll have to leave. And leave they will. Nobody wants to get up in the morning, go to work and then fail. If the job and behaviours you’ve specified mean they can’t win, they’ll join one of the 99% of other companies that don’t see this as important.

Encouraging trust (and vulnerability)

When we’re coaching teams through the Karpman Triangle and Lencioni’s ‘Five Dysfunctions Of A Team’, a lack of trust can show up. This might be at the root of all the drama that keeps happening. So, it’s crucial to shift the dynamic away from people behaving like victims and towards showing up with vulnerability. Instead of ‘It’s not my fault’, 13 weeks down the line, you want them to tell you they’re struggling in week 1. But this will only happen if that person feels safe enough to admit failure. This is crucial – so crucial that Lencioni put vulnerability-based trust as the foundation of his pyramid (see image above).

The team might need to work on this. And it’s hard. They’re going to need to build muscle around giving direct feedback. There needs to be an understanding that they’re doing this because they care about each other. A helpful exercise is to ask each member of the team to rate the different pairings of relationships – John and Susan, Betty and Susan etc. Quite quickly, it’s obvious where the issues lie. When we did this with a team recently, everyone agreed it was one particular pair of people that had issues. It came as a complete shock to the people concerned. With another client, there were three pairings that were considered the weakest and they all contained one particular guy. He was mortified. However, you need this objective measurement before you can sort it out.

It’s clear to us. The difference between good and great companies is the ability to have difficult conversations. That and that alone will give you the edge. We can put in a framework, help you be more efficient, plug some gaps and come up with a great business model. But unless you can confront the brutal realities of true Level 5 leadership, you’re unlikely to succeed.

Written by business coach and CEO mentor Dominic Monkhouse. Read his new book, Mind Your F**king Business here.