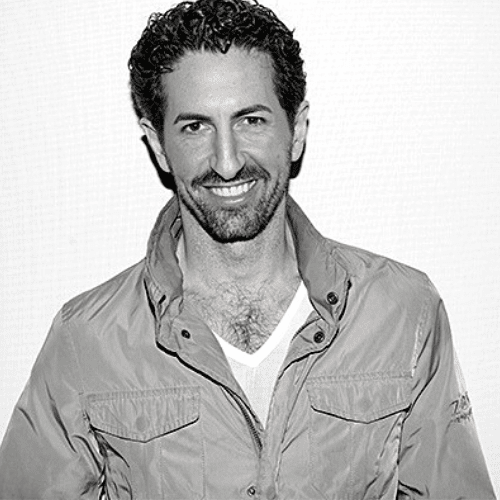

Today’s guest is Professor Moran Cerf, a neuroscientist and business professor at the Kellogg School of Management and the neuroscience program at Northwestern University. He holds a Ph.D in neuroscience from Caltech, an MA in Philosophy and a B.Sc in Physics from Tel-Aviv University.

Moran has had a varied work history, prior to his academic career, he spent nearly a decade in industry, holding positions in computer security (as a hacker), pharmaceutical, telecom, fashion, software development, and innovations research.

Now he’s interested in how we can use the brain to leverage better business opportunities. He is currently teaching MBA students how to change behaviour, how marketing works and how people think and make decisions. He is a firm believer that social engagements are more powerful than the addictive lure of drugs or our devices, and his goal is to make the world a more optimistic place.

Listen to hear him talk on today’s podcast about:

- How his work addresses questions such as: “How are conscious percepts formed in our brain?”

- Why social interactions are so important to our brains

- Why his goal is to make the world a more optimistic place

- Your brain is a storytelling machine

- Why we only have control over 15% of our brains, and that doesn’t include the decision-making part

- How to beat an addiction to social media

Links:

Today’s guest is Professor Moran Cerf, a neuroscientist and business professor at the Kellogg School of Management and the neuroscience program at Northwestern University. In his work, Moran looks at how we can harness the knowledge we have about the brain to further improve understanding of how we make decisions, both as customers and businesses.

More importantly, he was recently named one of the “40 leading professors below 40”. Here are a few of his insights.

Making choices

When you make a choice, if you then have to explain that choice, you only have conscious access to a tiny part of the decision-making process. Whilst you might think you were consciously choosing your choice, a thousand things went through your mind during the process to which you weren’t privy.

If you look at your brain as a pie chart, we only have access to 15% of this pie chart, that’s the part we have control over. The remaining 85% of our brain we have no control over, things such as breathing or our heart pumping. Most people don’t realise that the ability to integrate complex information into a decision is in fact one of those things that we have no control over.

In short, none of us have full access to our brains. Asking someone to explain their choice isn’t futile, it’s just incomplete. If you want to know how someone made their choice, you have to look at their brain to get the full answer.

And our brains are vulnerable to making choices, in fact, unless the choice is something monumental like picking your wife out of a line up, we don’t normally realise we are doing it, our choices are so insignificant. But if we are asked to explain our choice, we will all defend it with what we think are rational decisions.

Companies exploit our decision making

When was the last time you bought something based on a recommendation that “people like you bought it”? Moran says the joke is going to be in 20 years time we will realise there was a glitch in the system, and in fact no one like us bought the same things we did.

We are being influenced and encouraged to stay in our spheres of familiarity where we can be controlled and our choices can be made for us. Think of Netflix or Amazon recommending shows based on your previous viewing data.

Who is better at making a choice: people vs algorithms

When a New York Stock Exchange trader makes a choice, he thinks he knows what he is doing, but the 85% that goes into the choice is not something he has any control over. However if asked to explain why he’s made his stock choices, he will try and explain his reasoning using factors within his control.

According to Moran, if we are to rely solely on algorithms, as opposed to gut feelings, we still won’t understand the decision making process any better, because we don’t understand what they’re doing—it’s just too complex.

When asked what he wishes he knew when he was younger, Moran says he would go back to his 17-year-old self and tell him to change what he does entirely every 10 years. He is scared of change, but things always work out.

Book recommendations: